I should start by saying that I absolutely loved my trip to Mali! It’s a country with a rich cultural history, amazing architecture, great music and bags of potential. People were welcoming and friendly, and everyone seems pretty happy to see us.

But it also has a lot of problems with malnutrition and inadequate sanitation, and malaria is rife. The literacy rate is one of the lowest in the world, especially among women, half of whom are married before the age of 18, and about 90% of whom have been subjected to FGM.

Mali takes its name from the Mali Empire which was at its peak in about 1300 CE. It was the largest and wealthiest in Africa, and one of the wealthiest in the world at the time, and apart from this great economic success, Mali was a centre of Islamic culture and learning, with Timbuktu university being one of the oldest still active.

Yes – Timbuktu is is Mali!

Its sister city Djenné was also part of the trans-Saharan trade routes and itself a centre of Islamic scholarship and religious teaching. Both towns are famous for their adobe architecture, particularly the Grand Mosque in Djenné, and both have been designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Happily I did get to Timbuktu, but sadly wasn’t able to visit Djenné; despite extraordinary efforts by our people on the ground, the Ministry of Security just wouldn’t give us permission. The government is currently really wary of foreign spies and even visa approval to enter the country isn’t always guaranteed. So lots of areas remain out of bounds for tourists, not just for safety reasons.

Just a brief summary of Mali’s history to give you an idea of the situation today:

The Mali Empire disintegrated in the late 16th century, and became a collection of smaller kingdoms, the most significant of which was the Bambara. In fact the Bambara people remain the most populous ethnic group in Mali today and it’s the most widely spoken of 13 national languages – ‘Mali’ is the Bambara word for hippopotamus!

Then came the Scramble for Africa and France took control of this part of the world in the 1890s. You can still see some of the old colonial buildings in Bamako and classic French boulevards.

Independence came in 1960 followed by 30 years of dictatorship until a 1991 military coup ousted the government, a constitution was established and Mali became a multi-party democratic state. For 20 years Mali was widely held to be the most politically and socially stable country in Africa.

But then in 2012 there was a Tuareg rebellion aided by Islamist insurgents from overseas aimed at establishing a separate state in northern Mali. The government handled the crisis badly and was overthrown, the French and UN military were invited in, helping to retake much of the north.

But since then there has been another coup and then a further military takeover. Both the French and the UN have withdrawn from the country, and there is a transitional government in power, which has a fairly weak grasp on the region. So the conflict is ongoing, the government is employing Wagner mercenaries, has little support from the people and keeps pushing promised elections further out.

Travel for foreigners to Timbuktu by land and water is currently quite precarious, so we flew from Bamako for a morning.

The 12 of us, plus a local guide, were met by more than 30 armed Malian soldiers to escort us for the entirety of our visit. I think it was partly to keep an eye on us, and partly to look after us, but while it really did feel quite tense when we first arrived, by the end of our visit everyone was smiling and taking photos together, and the tension had completely disappeared.

The people of Timbuktu seemed as happy to see us as we were to see them – there were approximately 200 tourists in the previous year in the whole of Mali and not all of them are getting to Timbuktu.

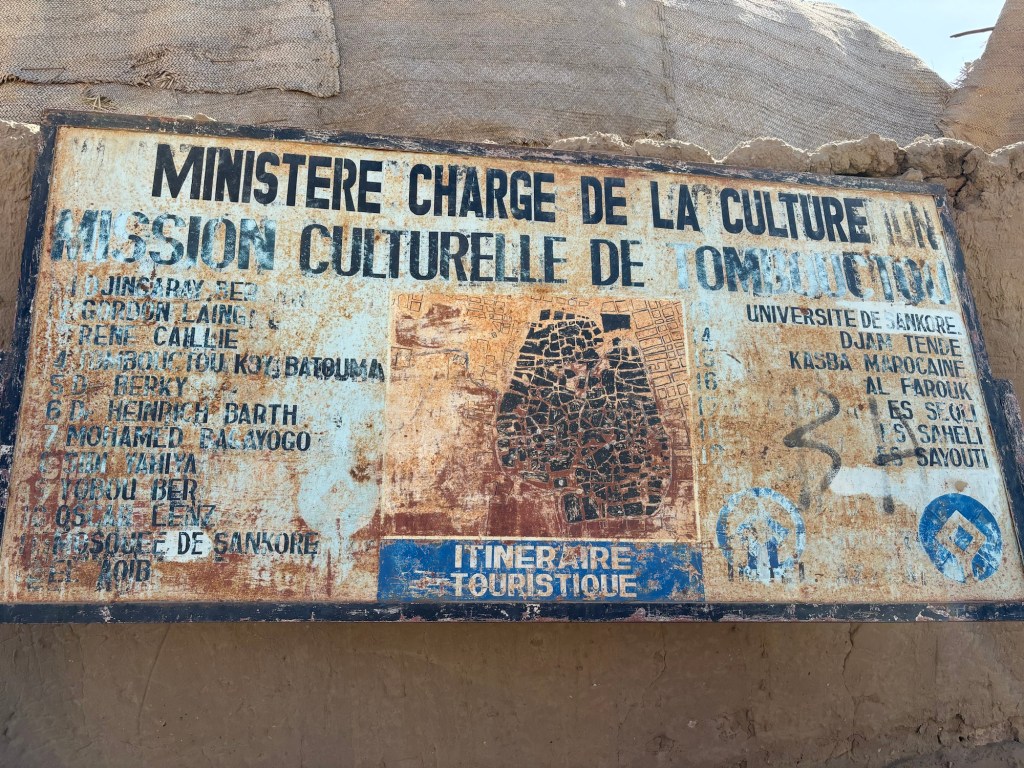

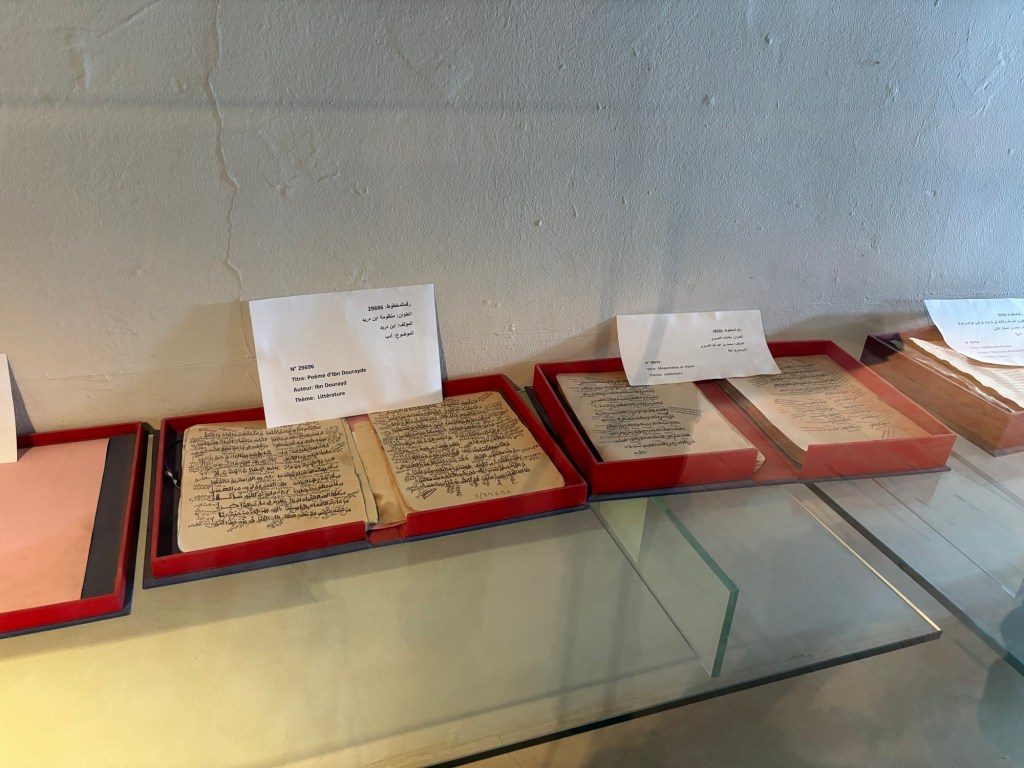

We were able to visit the Grand Mosque, the University of Sankore, the house of Alexander Gordon Laing (who was the first European to visit Timbuktu), the Ethnological Museum, the Well of Buktu and some of the Timbuktu manuscripts.

The visit to see the manuscripts was a real treat – not just to see the preservation work and hear from the man in charge of looking after them, but also because it was so heartwarming to see our military friends enjoying it and taking photos just as much as we were!

We had lunch in Timbuktu with music and dancing before being escorted back to the airport for our flight home to Bamako.

Back in Bamako which is a busy, dusty, crowded city full of people and traffic. There are lots of markets for food, household goods, artisanal goods, voodoo charms and medicines etc, but the most interesting was the recycling market where about 2500 people live and work turning stuff like broken cars, oil drums and rebars into cart wheels, cookers and nails.

This recycling is done out of necessity rather than principle to create much needed goods that otherwise couldn’t be afforded. Plastic bags and bottles aren’t recycled, and instead contribute to a huge amount of garbage everywhere in the country. The shoreline you see here in Mopti was typical of the banks of the Niger and Bani rivers and the majority of streets.

The ongoing conflict means the humanitarian crisis is real and frankly waste management is a low priority with so many other problems facing Mali; there is a large amount of poverty, many people have been displaced and education has been inconsistent and disrupted for years.

The average monthly wage is Mali is only EUR120. These ladies are selling a traditional breakfast of rice pancakes and beef foot stew to recycling market workers for about EUR 1 per portion. With an average of 5 or 6 children per woman in Mali, EUR120 is not enough to go round.

Many children need to contribute to the family income from a very early age.

There are a lot of children in Mali – it’s estimated that over half of the population of Mali is under 19 years of age. Wherever you go, you’ll end up with a group of children following you!

We weren’t able to make it to Dogon Country where there is fabulous countryside and hiking, but as well as visiting Timbuktu, Ségou, Mopti, San and Bamako, we also made a visit to Koulikoro. Here you can see the mountain of Nianankoulou, said to be where the 13th-century ruler Soumangourou Kanté disappeared after being defeated.

There’s also the mystical Niamè Fara or the Squatted Camel rock formation, which to be fair is considerably better that my photo makes it seem!

Close by are the Faramissiri Caves which house a sacred mosque visited by pilgrims annually. Families live here and there’s a madrassa and tablets for learning.

We also went camping and hiking in Siby, just south of Bamako and ate some amazing food prepared by the female camp cook. In fact most of the food in Mali was pretty good, such as beef, chicken, vegetables, rice, couscous, plantain and frites. There was also a lot of good fresh fish caught from the Niger River.

Mali is famous for its music and there are plenty of nightclubs and opportunities for listening and dancing. We went to hear Baba Salah play for over three hours one night which was a real treat, and also made it to one night of the Festival Ogobagna in Bamako.

My trip to Mali was so fantastic and I was really quite sorry to leave at the end of my holiday. There are many problems to fix without the right people in the right places to help fix them, but there is so much potential with its beautiful countryside and people, and rich and varied cultural heritage.

Mali is amazing, but it could be exceptional and I hope they find a way to break the current conflict soon and get back to those improvements that were being made before the rebellion knocked everything off track.

The next Dogon Festival, which is held every 60 years, will be in 2027. I hope by then Djenné is open and the whole country is accessible because overall it’s fair to say that J’❤️ Mali and I’d like to go back for another visit.